By Barry Saxifrage | Analysis | Published in National Observer July 5th 2021

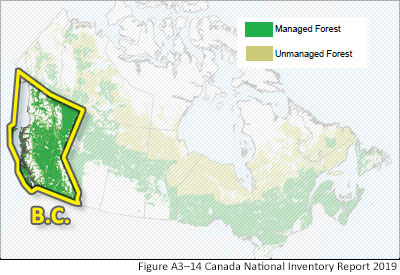

British Columbia’s vast managed forest is one of the most carbon-rich ecosystems on the planet. Its towering old-growth trees, in particular, are champions of carbon storage.

Historically, B.C.’s forest removed far more CO2 from the air each year than it emitted — storing the excess away in new growth. This valuable “carbon sink” helped slow the pace of our human-fuelled climate crisis.

And as an economic bonus, it also provided a free “carbon offsetting” service for all the wood harvested from it.

But B.C.’s forest has been struggling under a relentlessly rising assault by the four horsemen of forest apocalypse: drought, heat, insects, and wildfire. Now, with its trees increasingly under siege and aflame, the forest has begun dying faster than it is growing back. Its once vast carbon sink has been replaced by a rising flood of CO2 pouring out of it and into our already destabilized climate system.

That’s the troubling tale told by the data in B.C.’s official greenhouse gas inventory. To illustrate the emerging threat to our forest health, to our climate stability, and to the valuable “carbon-neutral” status of the wood cut from B.C.’s forests, I’ve dug into that government data to create a series of charts.

One thing these charts make clear to me is that our decades of foot-dragging on the climate crisis will not be cost-free. The era of climate consequences is arriving.

Steady and relentless

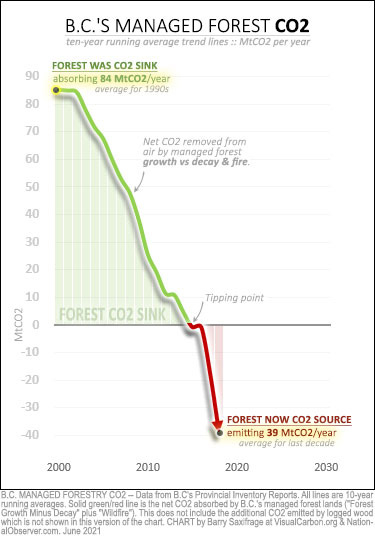

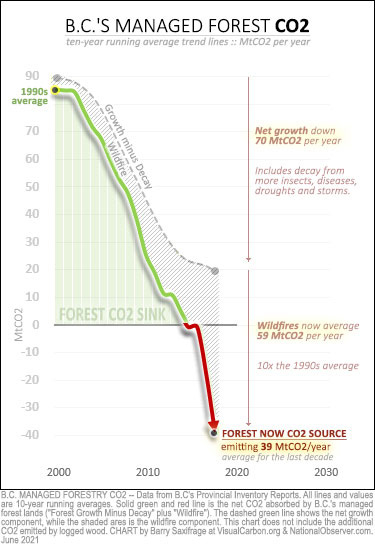

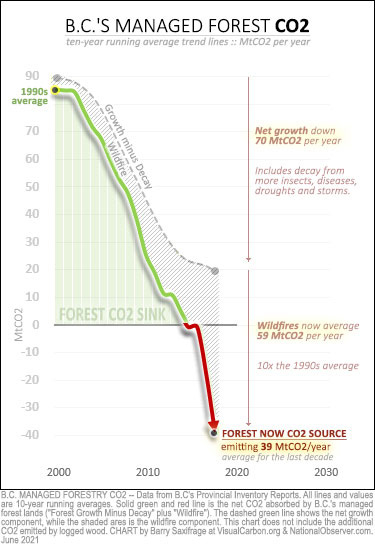

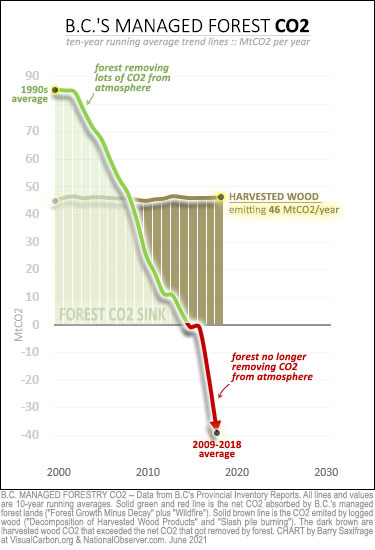

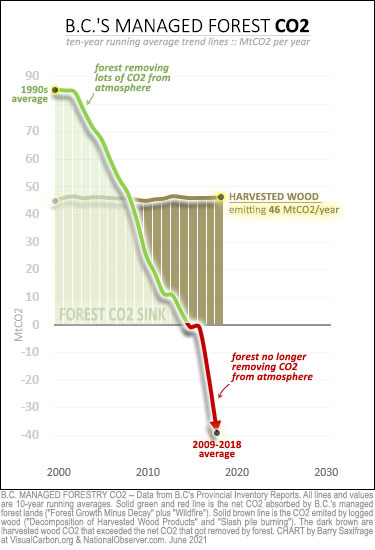

Let’s start by looking at the big picture — the CO2 balance in B.C.’s forest. It’s shown by the plunging line on my first chart. This doesn’t include the additional CO2 from logged wood, which we’ll look at later.

Before diving into the details, there is one geeky, but essential, point to explain. All my forest carbon charts in this article show a 10-year running average of the data. I’ve done this to show the underlying long-term trends that are unfolding in the forest.

What it means is that every point on a line, and every CO2 value, is the annual average for the 10 years leading up to it.

For example, that dot at the top of the green line shows B.C.’s forest removed an average of 84 million tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2) per year from the atmosphere during the decade of the 1990s.

Compare that to the dot at the bottom of the red part of the line. It shows that B.C.’s forest emitted an average of 39 MtCO2 per year over the previous 10 years (2009-2018).

One more important takeaway from this first chart is how steadily and relentlessly the collapse has played out. This huge decline isn’t the result of a few unconnected freak events. As we will see below, it has been driven primarily by the steady and relentless changes to the climate that humans have been cooking up with our fossil fuel CO2.

The full impact in the atmosphere

The full climate impact of this carbon collapse averaged 123 MtCO2 per year over the last decade. That’s the CO2 change between the two ends of that plunging line on the chart above.

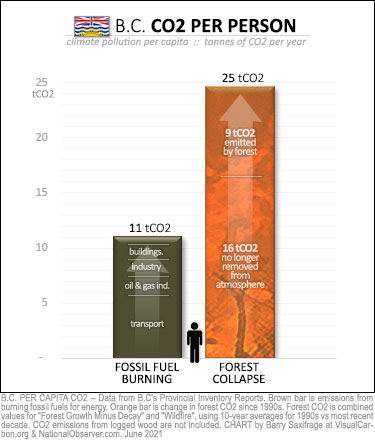

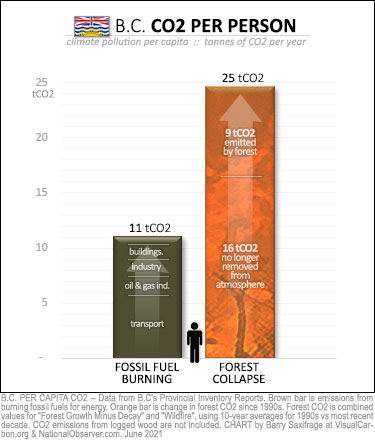

For scale, that works out to an extra 25 tonnes of CO2 (tCO2) per year in the atmosphere for each British Columbian.

That’s more than double the CO2 emitted by all fossil fuel burning in B.C.

Around 16 tCO2 results from the forest no longer removing that much CO2 from the atmosphere each year.

The other nine tCO2 is what the forest now emits into the air instead.

To me, such a huge new flood of CO2 is a flashing red light — warning us that we are in danger of losing control over the climate crisis here in B.C.

Climate scientists have long warned that unchecked climate pollution has the potential to push major ecosystems past tipping points in which their continued collapse becomes difficult, expensive or even impossible to stop.

And the more carbon an ecosystem holds — like the billions of tonnes stored in B.C.’s forest — the greater the threat it poses should we recklessly push it past its carbon tipping point.

The role of climate change

To better see the role climate disruption has played in the carbon collapse so far, let’s dig down one more level into the government’s data.

The B.C. inventory breaks the forest CO2 balance into two parts — “Forest Growth Minus Decay” and “Wildfires.” My next chart shows the role of each.

The first part, “Forest Growth Minus Decay” is shown by the dashed grey line on top.

As you can see, net forest growth has declined by an average of 70 MtCO2 per year since the 1990s.

This decline has been driven primarily by rising temperatures and droughts brought on by global heating. Rising temperatures have been favouring increased insect and disease outbreaks, while increasing droughts have been weakening the trees’ ability to fight back. It’s a one-two punch.

The most famous of these climate-fuelled outbreaks has been the wholesale slaughter of B.C.’s most common tree — the lodgepole pine — by native bark beetles. Climate shifts led to a 100-fold increase in these beetle populations. So far, these rice-sized insects have killed half the mature lodgepole pine trees in the province and reduced the growth in countless more.

The second part of the forest CO2 balance data is for “Wildfires.” This is shown by the shaded grey area on the chart.

In B.C., CO2 from wildfires has surged ten-fold compared to the 1990s — leaping from five MtCO2 per year back then, to an average of 59 MtCO2 per year over the last decade. This has also been fuelled primarily by global heating. Rising heat and droughts are increasing the kinds of extreme fire weather conditions that explosive megafires require.

’10 to 100 times faster’

Troublingly, the climate siege on our forests shows no signs of letting up.

National Resources Canada highlights the rising climate threat in its latest State of Canada’s Forests report, stating: “Scientists predict that increasing temperatures and changes in weather patterns associated with climate change will drastically affect Canada’s forests in the near future. With the rate of projected climate change expected to be 10 to 100 times faster than the ability of forests to adapt naturally.”

The report goes on to say seedlings are especially vulnerable. As the forest tries to grow back, young trees will be increasingly unfit for the new climate conditions.

Trees can’t move. That might seem obvious, but when extreme weather hits, being able to move can be the difference of living and dying. Humans and animals have the relative luxury of becoming climate refugees, where they can at least try to move to a more livable area. Trees can’t. As we pull the climate rug out from underneath trees, they stop growing, die or burn in place. Often all three.

Because of a feature of global heating called “polar amplification,” the climate is changing much faster in Canada’s northern forests than in more southern ones. But even many of the forests to the south are starting to suffer major climate impacts.

For example, California forests are also under siege by a staggering rise in extreme wildfire. Last year alone, a record four per cent of the entire state burned. Just one of those fires is estimated to have killed 10 per cent of the remaining ancient Giant Sequoias. These trees are specially adapted to withstand fire — surviving through centuries of wildfires in the cooler and wetter “old climate” that we’ve now thrown away.

And to the east, in the Colorado Rocky Mountains, global heating is driving wildfires to the highest level in millennia, according to a new study. In a University of Wyoming news release, one of the study authors warned of the rising ferocity of wildfires: “Forest management had little impact on the 2020 fires. They burned designated wilderness and national parks with limited fuel management, heavily managed areas with substantial timber removal, and intact forest and areas with extensive beetle kill.”

Under current trends, the study estimates that every forest in the region could burn during the lifetime of today’s children.

Humanity’s accelerating climate pollution has grown so massive that it’s unleashing a horde of invisible chainsaws cutting their way through the world’s forests. These phantom chainsaws are ignoring our imaginary boundaries, our forest plans, and our hopes for a stable climate.

Logging’s new 46-million-tonne problem

So far, we’ve looked at the CO2 that humans are indirectly causing in B.C.’s forest through our climate pollution.

Next, let’s look at the additional CO2 humans are directly causing by logging that forest. Once a tree is cut, the carbon stored in its wood turns back into CO2. This happens either when the wood is burned, or when it rots at the end of its use.

B.C. reports the amount of CO2 emitted by the wood harvested in the province. I’ve added a brown line to the chart to show it.

Over the last decade, the wood logged in B.C. emitted an average of 46 MtCO2 per year. That’s a huge amount of CO2 — far exceeding emissions from any other sector in B.C.’s economy.

Historically, however, B.C. has exempted this source of CO2 from both the provincial carbon tax and from the province’s climate targets.

That’s because, historically, B.C.’s forest removed that much from the atmosphere each year. When the forest removes the logged carbon each year, it’s easier to argue that the wood is “carbon-neutral.”

But as the government’s own data shows, the forest is no longer removing more CO2 from the atmosphere than it emits.

The logging industry hugely benefited from the free CO2-removal service the forest used to provide. To appreciate how great a deal that free service was, consider that a company like Climeworks in Iceland charges $1,000 per tonne to remove CO2 from the atmosphere using machines.

The carbon collapse in the forest has left the logging industry in a situation where it is now cutting trees from a forest that is emitting CO2. That might make it a lot harder to convince customers that this is a climate-safe and sustainable product.

Will their climate-aware customers still buy it? Will climate-concerned governments still bless it with “carbon-neutral” status in their climate policies? Will provincial and federal climate policies continue to exempt the CO2 from this harvested wood from carbon taxes and climate targets?

The consequences of foot-dragging on climate action are starting to pile up. As the climate crisis keeps getting worse, the consequences will too.

The gift of healthy forests thriving under a stable climate is a wondrously spectacular, and wondrously valuable, natural legacy. We have been foolishly destroying that magnificent heritage with our failure to rein in our climate polluting. If we continue to cook our forests past their carbon tipping point, the price will be high for generations to come.

B.C.’s other climate pollution

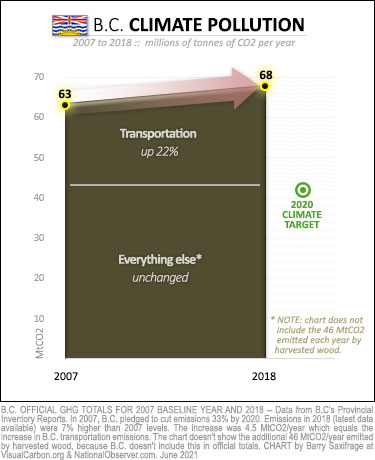

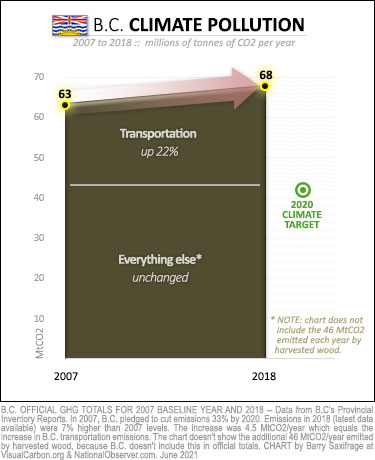

I’ll wrap up with a quick look at what the B.C.’s greenhouse gas inventory says about the rest of the province’s emissions.

My next chart shows the total of all the other sources of climate pollution in B.C. This is the “official” total. As noted, this excludes the forestry CO2 humans are causing either directly (logging) or indirectly (climate pollution).

Back in 2007, the British Columbia government pledged to cut these official provincial emissions 33 per cent by 2020. Following through on that promise would have seen emissions fall to meet the green bull’s-eye on the chart.

But, as you can see, B.C. allowed climate polluting to increase instead.

I’ve separated out transportation emissions to highlight that rising fossil fuel burning in vehicles has accounted for all that increase. One cause of this is that Canadians — amazingly at this point in the metastasizing climate crisis — are choosing to buy the world’s most climate-polluting new cars and trucks. The average new passenger vehicle in Canada will emit 66 tonnes of CO2 out its tailpipe over its lifespan.

Tailpipes are now doing double duty as phantom chainsaws. And in Canada, we apparently prefer them super-sized.

Plan B?

B.C.’s climate pollution data tells an increasingly troubling tale.

Climate targets have been ignored.

Climate policies are so weak that emissions keep rising.

The province’s dominant ecosystem, its majestic forest, has been so battered by climate pollution that CO2 is now flooding out of it — adding to the climate crisis.

And yet, logging in this forest continues at “old climate” levels. The 46 MtCO2 per year in logging emissions piling up in our atmosphere continue to be exempt from climate policies and targets.

Even the tiny sliver of B.C.’s carbon-rich, old-growth forest that still remains is being aggressively targeted by the logging industry chainsaws, while the government clears the way by arresting hundreds of its own citizens who are trying to save what little is left.