Reposted from West Coast Environmental Law (WCEL)

August 9, 2021

Author: Erin Gray – Staff Lawyer

No matter where you live, it’s likely that the climate crisis has been top of mind this summer – especially with the August 9 release of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report. With wildfires ravaging the West Coast and the heat dome that traversed the country last month, to droughts and water shortages across most of Western Canada and the Prairies – it’s clear that we must tackle the twin climate and biodiversity crises from all angles. One important angle is marine protection; as the ocean sequesters carbon, produces oxygen and regulates climate and weather, ocean protection can and must be included in climate change mitigation and adaptation planning.

In the coming months, the federal government intends to conduct a public consultation on an action plan for a proposed Marine Protected Area (MPA) Network in the Great Bear Sea (the first such network in Canada!) – and we want you to be ready.

Ocean mismanagement and climate change

On June 29, 2021 the federal Fisheries Minister announced an unprecedented long-term closure of nearly 60% of commercial salmon fisheries on the Pacific coast in order to “give salmon a fighting chance at survival.” Salmon stocks have steadily declined since the 1950s: for example, sockeye salmon stocks have declined 90% since 1950, and chum stocks have declined 94% since 1954. The reasons for this are complex, and involve climate change, habitat degradation, and harvesting impacts. The Minister warned that it will likely take multiple generations for the stocks to rebuild and the decline has had devastating impacts on coastal communities, commercial fishers and Indigenous food, social and ceremonial fisheries.

The day after the announcement, a climate change-induced heat dome covered the province, causing the hottest temperatures on record in Canadian history. A UBC marine biologist calculated that the resulting rise in ocean temperatures, particularly in shallow waters and intertidal zones, may have killed more than a billion marine animals in the Salish Sea. BC shellfish harvesters incurred catastrophic losses that could put some harvesters out of business for years.

Clearly, our current ocean management practices are not adequately addressing the coinciding climate and species extinction crises. But what can be done differently?

MPA Network in the Great Bear Sea: reason for hope

We’ve written before about the MPA Network being developed in the Great Bear Sea. This collaborative project, undertaken by Indigenous, federal and provincial governments, is an example of what can be done to manage our oceans in the face of climate and ecological uncertainty.

(Photo with permissions: Living Oceans, 2014)

The area is also known as the Northern Shelf Bioregion and is a place of profound ecological and cultural richness. It is directly impacted by the climate crisis and species collapse; for example, salmon runs have declined considerably (a number of the salmon fisheries closures mentioned earlier are in the area), and this also impacts the Great Bear Rainforest, as a salmon dependent forest.

The Great Bear Sea MPA Network is an example of co-governance and Indigenous leadership. Seventeen Indigenous governments have worked with the federal and BC governments on developing the network, which will link and amplify the benefits of several existing protected areas: Gwaii Haanas Marine Conservation Area Reserve and Haida Heritage Site, the Scott Islands Marine National Wildlife Area, the Hecate Strait/Queen Charlotte Sound Glass Sponge Reefs, and the SGaan Kinghlas-Bowie Seamount MPA.

Benefits of marine protected areas

MPAs are areas of the ocean permanently set aside from harmful human activities in order to achieve conservation goals. Standards and regulations vary across MPAs; from limitations on fishing in certain areas, to complete no-take zones (where no commercial and recreational fishing is permitted) and prohibitions of habitat disturbance by industrial activity (such as shipping and oil and gas activities).

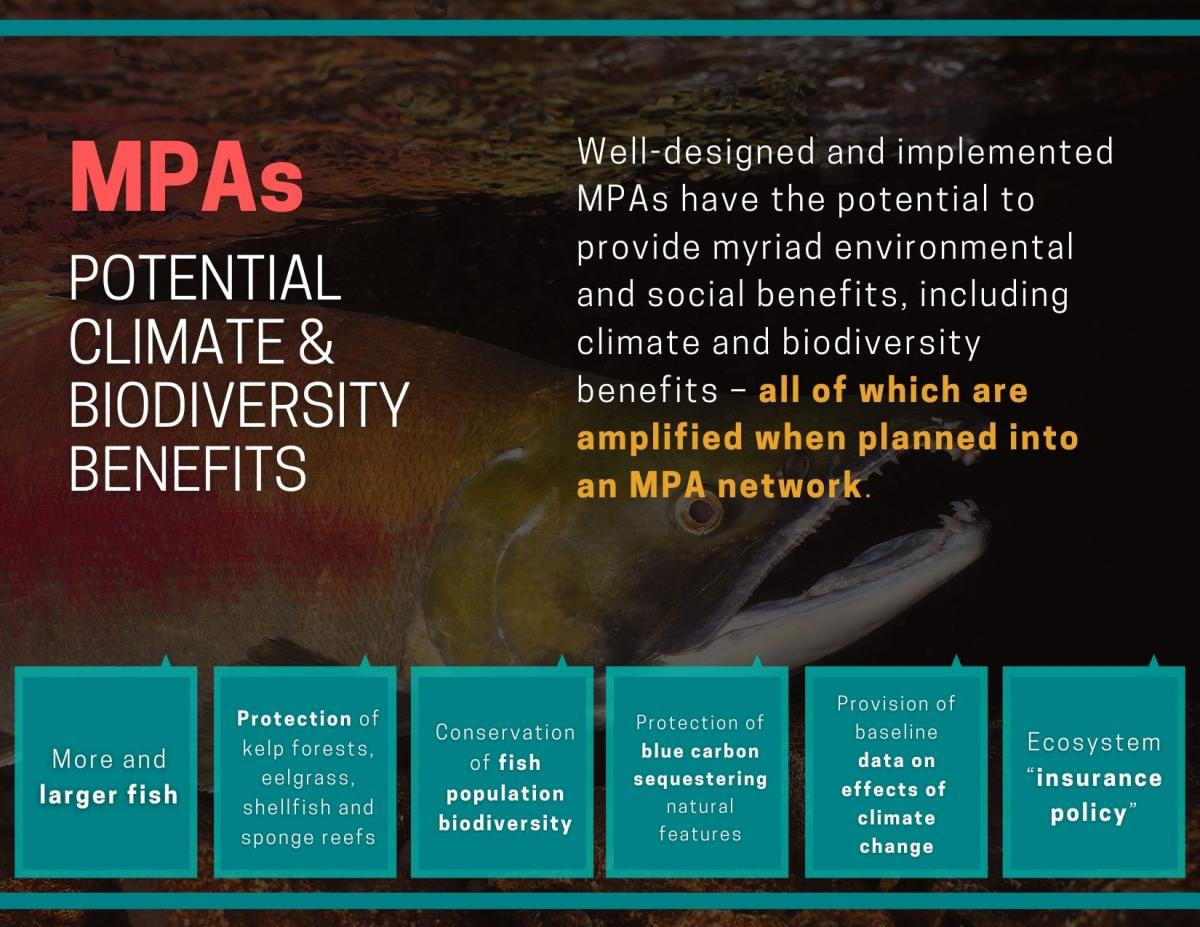

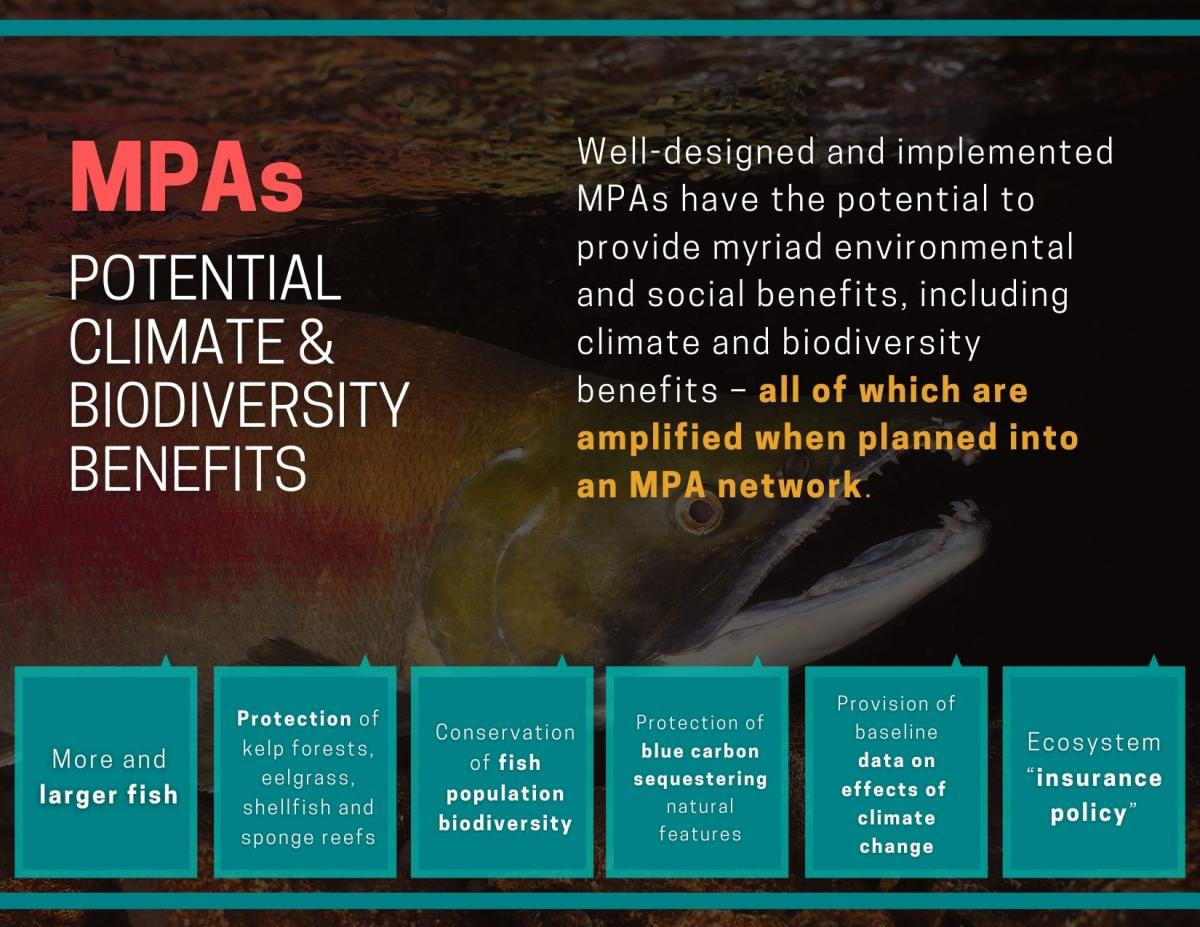

Well-designed and implemented MPAs have the potential to provide myriad environmental and social benefits, including several related to mitigating and adapting to the climate and biodiversity crises. MPAs can:

- Result in increasing numbers of fish and larger fish, as reducing or removing the pressure from fishing allows fish to reproduce, spawn and grow unabated;

- Protect important, habitat-forming species, such as kelp forests, eelgrass, shellfish and sponge reefs;

- Conserve the biodiversity of fish populations, other marine life and their habitats, increasing the resilience of ocean ecosystems to the harmful impacts of climate change;

- Protect “blue carbon” sequestering natural features, such as vulnerable seagrass meadows, which should slow the decline they are experiencing due to coastal development and warming ocean temperatures – as well as preventing the release of stored emissions from these areas; and

- Offer important baseline data when studying the effects of climate change impacts (such as ocean acidification) and thereby acting as “living laboratories” for understanding how these impacts affect regional ecosystems, cultures and economies in areas where human activities are restricted or absent.

MPAs act as a sort of ecological insurance policy. As the lead author of a 2014 article published in Nature regarding MPA effectiveness said, “protected areas provide some insurance for future generations against ecosystem collapse.”

A network of MPAs amplifies the benefits of MPAs and conserves biodiversity in the ocean: the network functions like a corridor of wild spaces on land, connecting important habitat areas over a large geographic region. MPA networks aim to include a greater diversity of habitats than a single MPA can, and can buffer against localized impacts in a single MPA by protecting similar habitats and species across a larger area of the ocean. Networks can also provide reference areas for monitoring the effectiveness of management actions across multiple protected areas.

There are plenty of real-world examples of the climate-related benefits of MPAs being realized. In Baja California, Mexico, despite climate-related pressures, the pink abalone population remained stable within protected reserves because of the large body size and high egg production of the protected adults. And in Northern California, a study on restoring kelp forests uses the nearby MPAs as control areas in which no human manipulation occurs, which aids in restoring those carbon sequestering natural features. And the benefits of creating MPA Networks are recognized worldwide. California implemented a state-wide MPA network in 2012, and is already showing some positive ecological effects, especially in the older protected areas. New Zealand is in the process of implementing MPA networks around its coastal waters.

What’s next?

After decades of co-leadership between Indigenous, federal and provincial governments, the federal government intends to release a draft plan for the Great Bear Sea MPA network to public consultation in the coming months.

Map: Proposed MPA network across Canada, DFO, 2018

As recent events have demonstrated, permanent ecosystem protection cannot come soon enough. And since this will be the first MPA network in Canada, it can also serve as an example for similar networks being considered on the East Coast and Arctic.

We cannot let the memory of this summer’s climate impacts fade as the seasons change; we must ensure that the process is not slowed down further or deprioritized, and that a strong Great Bear Sea MPA Network is implemented.

Top photo credit: James Wheeler on Unsplash